Dr. Ashira Blazer was still a student at the Baylor College of Medicine when her understanding of lupus, a debilitating autoimmune disease, suddenly hit close to home. Her cousin had unexpectedly missed Thanksgiving dinner that year due to an illness. At the time, Blazer was studying immunology and reading about this disease extensively.

“My cousin told me she had been sick. At first, I thought maybe she meant she had a cold or a stomach bug,” Blazer said. “But then, she started listing her symptoms, and I referenced my immunology textbook, thinking, ‘This could be lupus.’ I took her to my professor at the time and went with her to an appointment. She ended up being diagnosed.”

Fortunately, Blazer’s cousin had access to a knowledgeable family member and trusted health resources to help her arrive at a timely lupus diagnosis. Unfortunately, that’s not the case for many Black women who live with lupus.

Lupus is a chronic autoimmune disease that disproportionately affects women of color, particularly those of African descent. It affects various parts of the body, leading to fatigue, skin rashes, fevers and pain or swelling in the joints. Its most common form, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which impacts the lives of more than 300,000 Americans, causes the immune system to attack its own tissues, leading to widespread inflammation and organ damage.

“Lupus is a top five cause of death for African American women due to chronic illness in that younger period between the ages of 15 and 24. It stays in the top 10 for African American women through the fourth decade of life,” Blazer explained.

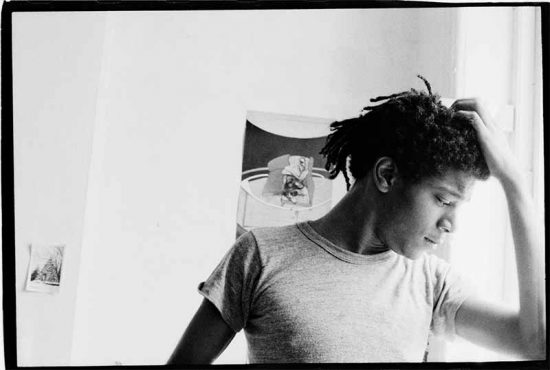

Dr. Blazer, now a renowned rheumatologist and assistant professor at the Hospital for Special Surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine, is dedicated to shining a light on lupus diagnosis and treatment disparities. Blazer’s work focuses on the biological and genetic determinants of lupus severity in patients of African ancestry. She has forged multiple international collaborations with rheumatology programs in West Africa, spearheading the development of unique bio registries in Accra, Ghana and Lagos, Nigeria.

Though lupus research continues to progress, Blazer believes there is more the medical community and individuals can do to stem the disproportionate impact lupus has on Black women. That starts, she says, with understanding the roots of its inequities.

Illuminating Disparities in Lupus Diagnosis and Treatment

Lupus is a heterogenous disease. No two cases are the same. Due to its complex nature, lupus is typically coupled with other comorbidities, like fibromyalgia, making diagnosis and treatment difficult. Additionally, systemic healthcare inequities exacerbate issues of identification and treatment for minority groups.

Early foundational research about lupus didn’t include many people of color. Therefore, physicians continue to struggle to identify the disease in these populations. The “butterfly rash,” a telltale sign of lupus, doesn’t appear as much in people across the African diaspora, says Blazer. Meanwhile, coin-shaped “discoid” lupus rashes are harder for physicians to identify on darker skin tones (building on an all-too-common theme within the medical community at-large).

Dr. Blazer’s first piece of advice for individuals? Know the signs.

“Common symptoms include the swelling of your small joints, like in your hands, particularly in the morning. You have stiffness, difficulty moving, you’re dropping things, and you have certain rashes,” Blazer says. “If somebody is developing rashes of any kind or experiencing hair loss, that’s another telltale sign. Some people may experience chest pain which is also common.”

Navigating Bias and Empowering Self-Advocacy

Though no patient should have to navigate bias within the healthcare field, Blazer says people should act as self-advocates when approaching interactions with their healthcare providers.

“One way is to ensure you visit a quality healthcare center. This is easier said than done because many Black people live in areas with fewer rheumatologists,” Blazer noted. “Community and culture are also essential, particularly for Black people. And there are some very well-curated patient support groups either through the Lupus Foundation of America, the American College of Rheumatology or the Lupus Research Alliance.”

Blazer says there is little data on why lupus disproportionately affects Black women. However, research is leading to some clear points about what can increase the risk in the population.

Things like stress and exposure to infections like COVID—which also disproportionately impact Black people—can increase lupus flare-ups.

And to this point, there is a call for greater representation for treatment among Black people. While 40% of lupus patients are Black, Howard University is the only HBCU with a rheumatology training program and only 1% of rheumatologists self-report as Black.

Changing this reality is a part of Blazer’s work. She is working with other schools to set up training programs that will partner with HBCUs to increase awareness and the chance for more Black medical students to enter the field.

One way to advance that work is to have consistent conversations and promote advocacy for treatment, especially as it relates to Black people.

“Increased awareness will increase diagnosis, particularly in communities of color. But also one of the biggest struggles people have is that lupus is extremely isolating. So it’s something that people have a tough time talking about, and you can’t get support if you’re not talking about it,” Blazer said.

Given the isolating nature of the disease, Blazer also notes the importance of having a support group, whether friends, family or caregivers, to help patients navigate the healthcare system and be prepared to ask providers the right questions.

“Bring someone in your support network to your appointments. That sounds very small, but people living with lupus are often tired or have brain fog, so even remembering the care plan can be a challenge if you don’t have someone with you,” says Blazer. “Also, make sure you are having empathic interactions with your doctor. Do you feel like you understand the care plan and your doctor is truly listening to your questions or concerns? If not, then it might be worth trying to find another provider.”

And while challenges exist, it is essential to note that lupus is not a death sentence, Blazer says.

“Lupus patients should not lose hope after their diagnosis,” says Blazer. “Although it can vary from patient to patient, treatment plans are advancing, and the research is deepening.”

Click here to learn more about lupus and how to take action for yourself or a loved one dealing with the chronic disease.

To learn more about SLE directly from a lupus warrior living with the disease, click here.