As the U.S. housing market rebounds from a pandemic-related slowdown, there is still evidence of housing discrimination that continues to limit homeownership and rental opportunities for consumers of color and other marginalized groups.

It’s necessary to take stock of how far housing policy has gone to outlaw discriminatory practices, and what work remains to be finished.

What is housing discrimination?

Housing discrimination is any prejudiced actions against a consumer who is buying a home, renting a home or attempting to participate in other housing-related endeavors. Discrimination can be based on the following characteristics:

-

- Color or race

- Disability

- Familial status

- Nationality

- Religion

- Sex

People who identify as LGBTQ aren’t explicitly protected by federal law from housing discrimination. However, several states have outlawed LGBTQ housing discrimination, which includes making prejudiced housing decisions based on a person’s sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression. For a state-by-state breakdown, see the Movement Advancement Project’s nondiscrimination laws map.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Equal Access Rule guarantees equal access to HUD-specific programs without discriminating based on a person’s actual or perceived gender identity, marital status or sexual orientation. Housing-related institutions and organizations that receive funding from HUD or have HUD-insured loans, such as home loans backed by HUD’s Federal Housing Administration (FHA), are required to follow this rule.

Although there is federal legislation in place to protect people from discriminatory practices in the housing market, the issue hasn’t completely gone away.

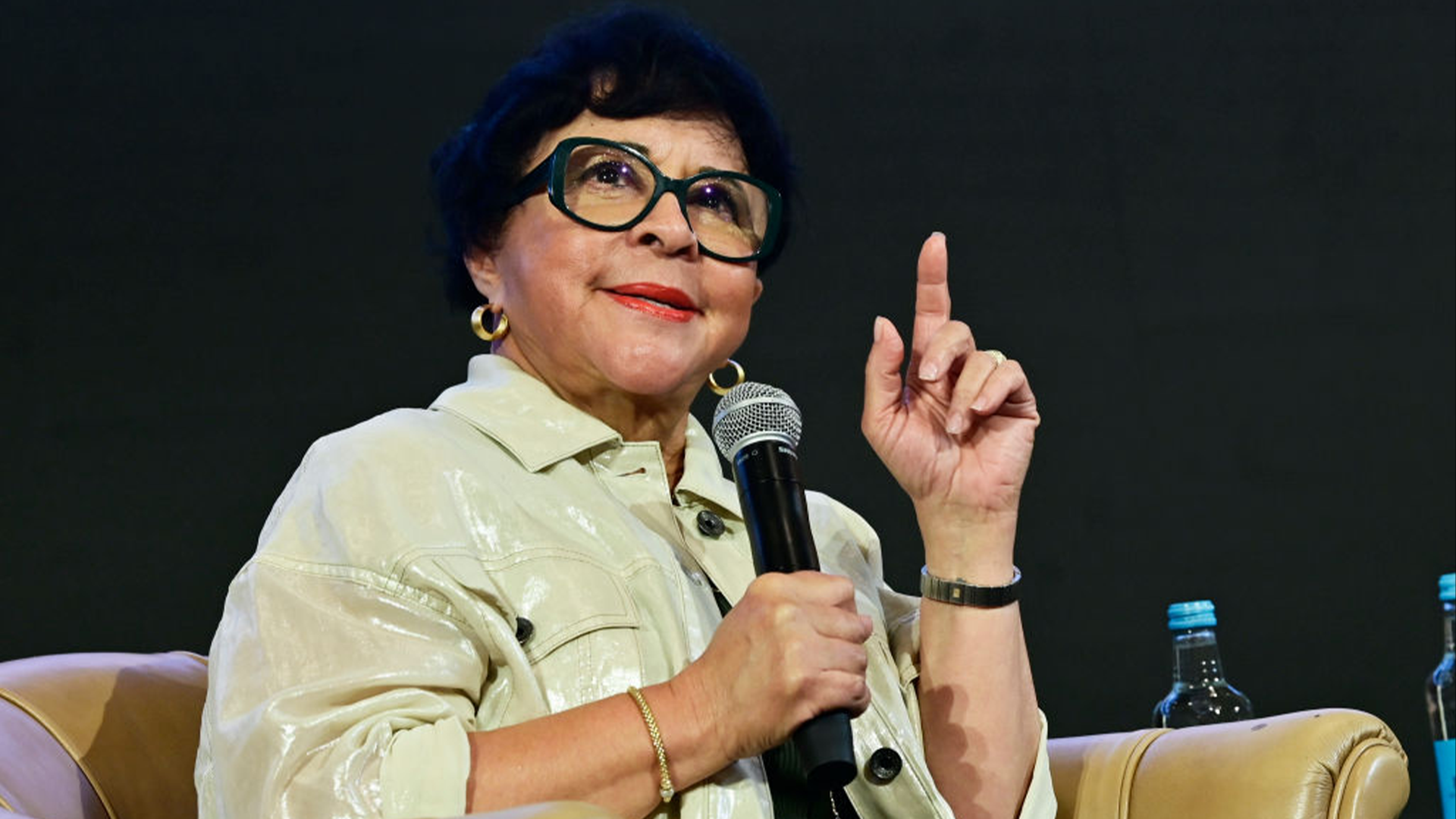

“(Housing discrimination) is a very real thing; it still exists in the country,” said Melody Imoh, policy and program director at the National Housing Resource Center (NHRC) in Philadelphia.

Housing discrimination examples

To better understand how prejudice can materialize in the housing space, here are a handful of housing discrimination examples — based on the characteristics listed above — for both homebuyers and renters, according to HUD:

| Buying a home | Renting a home |

|

|

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 explained

Current housing policy in the United States includes the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which is part of an expansion of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The legislation prohibited discrimination related to the financing, renting and selling of a home-based on national origin, race, religion, and sex, and was amended to include disability and familial status, according to HUD.

The Fair Housing Act’s protections apply to most types of housing, but may exempt the following limited scenarios:

-

- Owner-occupied homes with up to four units.

- Single-family homes sold or rented directly by the owner (without a real estate agent).

- Housing operated by private or religious organizations that limit occupancy to their members.

What is redlining in real estate?

A major form of housing discrimination that limited equal access to homeownership opportunities was called “redlining.” Redlining in real estate involved using maps to color code the neighborhoods in a given city based on their racial makeup. The maps were created by the government-sponsored Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) in the 1930s and their use in redlining became an illegal practice with the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968.

Neighborhoods outlined in green were considered the best, while areas outlined in red were concluded to be hazardous. Predominantly Black neighborhoods were outlined in red, and would-be homebuyers were often denied for mortgages in those same areas. Additionally, Black prospective homebuyers who wished to buy in predominantly white neighborhoods were more likely to be denied for a loan, even if they met the lender’s requirements. This effectively reinforced segregated neighborhoods and led to minimal investment in Black communities.

Redlining has lingering effects that continue to impact homeownership and access to wealth for Black communities. In fact, over the last 40 years, homeowners in historically redlined neighborhoods gained nearly $212,000 less in home equity than homeowners in greenlined neighborhoods, according to data from real estate brokerage Redfin.

David Young, director of capacity building at Housing Action Illinois in Chicago, has witnessed the lasting effects of redlining in his own community. He’s a resident of South Shore, which is south of Chicago’s downtown area.

“If you look at the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map from 1940, the area where I live is classified as yellow,” Young said. A neighborhood outlined in yellow indicates a “definitely declining” area, according to the HOLC color coding system.

“The reason why it was listed as declining is because you were seeing more African Americans and immigrants moving into the neighborhood,” Young explained. “So it started then to impact lending decisions that were made, that you still see nearly 100 years later impacting the loans that are made in this community.”

3 ways to strengthen U.S. housing discrimination laws

Here are some potential ways to reduce and eventually eliminate the ongoing practices that lead to housing discrimination, according to housing advocacy and policy experts:

Remove appraisal biases. Home appraisal bias refers to the practice of tying a home’s value to the ethnic makeup of the neighborhood surrounding it. “If it is a majority African American or Latinx neighborhood, with the same housing stock, you might see the values being significantly lower than (they) would be in a majority Caucasian community,” Young said.

Increase access to credit. Data from the Urban Institute show that in the under-35 age group, Black college graduates have a lower homeownership rate than white homeowners without a high school diploma. “Access to credit is not equitable,” said Ibijoke Akinbowale, director of the housing counseling network for the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) in Washington, D.C. One way to expand credit access is using rental history to build a credit profile, Akinbowale suggested. “People can have years and years of on-time rental history that’s not reported on your credit.”

Maintain federal protections. HUD proposed a rule to change how disparate impact is interpreted in the 1968 Fair Housing Act and what it means for mortgage lenders and other organizations. The disparate impact rule says a policy may be considered discriminatory if it disproportionately impacts any group — based on race, religion or the other protected characteristics mentioned above — no matter the policy’s intention. HUD’s proposed rule may allow certain practices to continue, even if it causes a disparate impact to a specific group of people. “Housing counselors would greatly suffer under this new rule, certain mortgage programs and debt relief programs may reject certain clients without adequate explanation and without consequence,” Imoh explained.

If you believe you’ve recently experienced housing discrimination, reach out to your local housing counseling agency or file a complaint directly with HUD.

This piece originally appeared on LendingTree.