Many may not know the story of Jeremiah G. Hamilton, Wall street’s first Black millionaire. Depending on the source, Hamilton’s 40-year Wall Street legacy is either frowned upon because of his alleged dishonest business practices or admired for his creative business acumen in a time where a Black man prospering on Wall Street seemed impossible.

What is undisputed is that Hamilton died in 1875 as the richest Black man in the United States with a $2 million estate that would be equivalent to about $250 million today, according to Shane White, author of “Prince of Darkness: The Untold Story of Jeremiah G. Hamilton, Wall Street’s First Black Millionaire.”

At the age of 20, Hamilton first made his mark on the financial world via a counterfeit coin scam where he transported a freight of fake coins from Canada to Haiti in order to sell them to New York businessmen, according to The Atlantic. When Haitian authorities caught wind of Hamilton’s counterfeit ring they issued a $300 reward for his apprehension. Hamilton managed to escape on a ship back to New York after hiding in Port-au-Prince for 12 days.

Word of the scandal soon got back to New York where the press slammed Hamilton deeming him the “Prince of Darkness.” However, the soon to be Black broker had gotten a taste of fast money and had no plans of stopping his climb to the top of the business world.

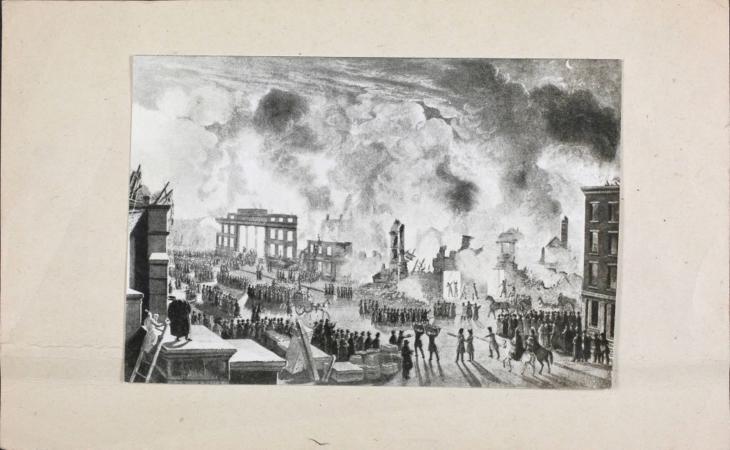

His ascend to greater financial heights would be catapulted during the Great Fire of 1835 where up to 700 businesses in Manhattan were burned to the ground. Hamilton took advantage of the fire and profited what would be worth $5 million in today’s currency by denying transactions of investors who could no longer present requisite paperwork that had been burned in the fire. He later invested the money in real estate, buying 47 properties in present-day Astoria including a local mansion and a 400-foot-long dock, according to The Atlantic.

Set on further increasing his net worth, it is rumored that Hamilton had a knack for insuring ships and then purposely sinking them in order to collect the insurance money. His methods would lead to New York marine insurance companies refusing to insure any ships operated by Hamilton. In fact, in 1843 the Atlantic Insurance Company sued Hamilton claiming he had illegally obtained $50,000 in insurance payouts. Hamilton beat the lawsuit after he claimed the insurance company had hired a hitman to drown him in the East River.

Not only was Hamilton known for dodging lawsuits he also used the legal action to amass more wealth. For instance, in the 1840s Hamilton started a legal war with Poughkeepsie Silk Company in hopes that the company would collapse leaving its revenue to shareholders like himself.

Continuing to use the courtroom as an avenue to income, Hamilton is most notably known for challenging business tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt in the 1850s for control over the Accessory Transit Company. Vanderbilt’s obituarist recalls the tycoon saying he “did not fear [Hamilton] because he never feared anybody,” but he most certainly “respected him.”

Vanderbilt wasn’t the only prominent businessman that respected Hamilton; in fact, most of Wall Street awed Hamilton’s business savvy techniques especially his stock market knowledge. Hamilton could be credited with the invention of one of America’s first hedge funds with the development of his investor “pool” in the 1860s where he would convince his non-Black counterparts to give him money to pick and invest in stocks. His pool became so popular that he began to request expensive champagnes and high-quality cigars from investors to better their chances of being accepted into his pool.

Upon his death — in May of 1875 — obituary headlines told two stories. Some described him as the “notorious colored capitalist” while others wrote, “his judgment in banking was highly esteemed, and he was often consulted by prominent bankers.” Hamilton was laid to rest next to his two daughters in their family plot at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery.

Jeremiah Hamilton’s ability to obtain financial success is a characteristic that should be admired despite any of his seemingly moral shortcomings. It’s as if Hamilton embodied a “by any means necessary” attitude long before Malcolm X preached the motto to the masses during the Civil Rights Era. He bought and traded stocks, owned properties, engaged in legal battles with those who once would be considered his owner, and made millions in the process.