This article was originally published on 05/17/2019

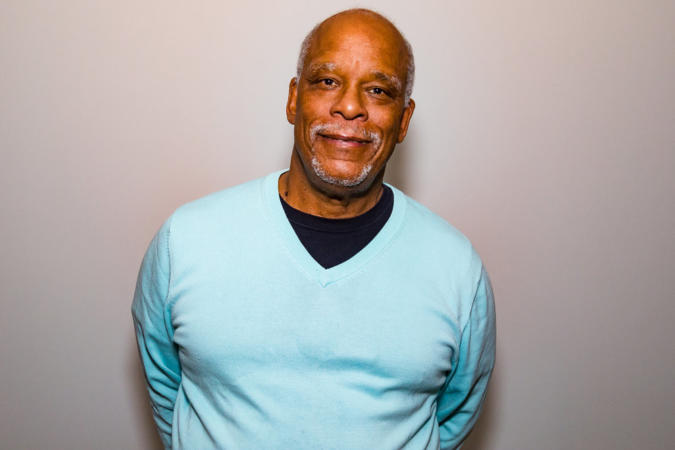

For his entire career, Stanley Nelson has told some of the Black community’s most important stories. From chronicling the murder of Emmett Till to outlining the history of HBCU’s, Nelson has given the world a window into some of America’s most iconic moments, giving voice and historical context to African Americans’ role in them. Now, Nelson is giving us a look at another aspect of Black life, one that has shaped the African American experience in a way few really understand.

In his new documentary, Boss: The Black Experience in Business, Nelson chronicles the contributions, successes, and inequalities that have followed African Americans as we’ve tried to pave our own way to success in an economy that wasn’t built for us to succeed. Through rarely seen photos and video, Nelson takes audiences through a journey of the first black entrepreneurs and how they bravely staked their claim in American life — and how that success and prosperity was stripped from them by those who were worried about their economy supremacy being taken away.

From his dissection of the Freedman’s bank — and the nationwide plunder that ensued — to the American tragedy that was the destruction of Black Wall Street, Nelson incites the feelings of anger and unfairness that African Americans felt then. Seeing images and hearing context from historians about how economic prosperity was taken from Black people is painful to watch, but Nelson says it’s necessary if we are to truly the understand the disadvantages African Americans faced in the earlier stages of our odyssey through American business and economics.

“When a film works well, it becomes an emotional experience,” Nelson told AfroTech. “That’s what we’re trying to do, take it [black business] out of something that’s academic to something emotional.”

Nelson’s film isn’t all tragedy and despair. There are several inspiring stories from some of America’s greatest business leaders. Early in the film we hear from Ursula Burns, the former head of Xerox who was the first Black woman to serve at the helm of a Fortune 500 company. She walks audiences through her journey of rising above poverty and starting out as an intern and working her way through a white, male dominated world to be the boss. The film also features business titans like Robert Smith, founder and chairman of Vista Equity Partners and the richest African American in the U.S. Through these stories, Nelson shows us that although the earliest Black business leaders faced insurmountable inequality, their sacrifices were not in vain.

“We’re talking to them as African Americans. What it means to be an African American in business and the struggles that they had to go through, the resiliency they had to have and what it is that helps them push through as black folks.”

For Nelson, the story of Black business in America is also his story. He grew up in a family of entrepreneurs. His grandfather was Madam C.J Walker’s business partner and his father owned his own dental practice in New York. Seeing their lives as entrepreneurs is part of what sent Nelson on a year’s long journey to tell the story of African Americans in business.

“I’ve known the story of Black people in business all my life,” Nelson said. “It’s a story that was talked about in the family and passed down and that we all knew. So it wasn’t a surprise to me that African Americans from an early time were part of business and involved in business and were creating their own destinies.”

Nelson wanted the film to be historical, as shown through reams of archival footage and lengthy interviews with scholars like Mersha Baradaran and Juliet Walker. But he also wanted it to be contemporary and include the efforts of today’s African American trailblazers. He says traveling through time and finding themes across generations of Black entrepreneurship was a unique challenge of making the film.

“So the trick was, how does that work? And one of the things we thought to do was to pick a couple of industries and say there have been a couple of industries that have been constant for African Americans, and maybe that can help tie the film together.”

One of those industries is haircare. He makes ties between Madam CJ Walker and Rich Dennis, the head of Shea Moisture. He evokes that same strategy with publishing, mentioning Ida B. Wells and her triumphs near the beginning of the film and rounding it off with the founding of Black Enterprise and Ebony magazine closer to the end.

Nelson spends a lot of time on the press in the film. He talks about it not only as a megaphone for chronicling and bearing witness to the Black experience, but as a crucial engine in driving Black business and economics forward.

An entire section of the film is dedicated to the Chicago Defender and how its coverage of the city inspired people to leave their southern homes for a new life in the north. Although The Defender didn’t start Black migration, the words read by people outside of Chicago made them want to travel to greener economic pastures, a mission of the paper’s founder, Robert Abbott. Abbott, like many other business leaders in the film, saw a greater mission than money when building their empires.

This is where Nelson’s mastery really shines in the film. He portrays the broader mission of Black business titans in a way that makes it real and digestible for audiences. He explains that, while the earliest Black businesses where about making money, they were equally dedicated to making things better for their communities, a theme that reigns true in the Black business community today.

“One of the keys for us for the whole film became that idea of doing well and doing good at the same time. So, one of the things that we found was that if you go across almost any industry that was kind of a constant for black folks. The idea of you do well for yourself but you also do well for your community.”

Another large portion of the film is dedicated to music and how it was a pathway to economic prosperity for Black people in the 1960s. Nelson chronicles the rise of Motown and Berry Gordy’s transformation of the industry so that Black people had equity in the culture they were driving. He then walks viewers through the rise of hip-hop and how it gave birth to entrepreneurs like Jay-Z and Puff Daddy, a segment he says was absolutely crucial to creating the film.

“I think it’s important that they be recognized not only for their music, but as business people,” Nelson said. “They’re making serious money and they’re doing it in the way black people have always done, which is figuring out a place that the majority population doesn’t see and doesn’t think about.”

Nelson begins the film by talking about farming and how that was one of the main ways the earliest Black entrepreneurs accumulated wealth. He ends it by talking about the next great frontier, tech, and how challenges of the past creep up for people in the industry today, whether through diversity issues at the world’s biggest tech companies, or the lack of VC funding for Black owned tech startups. Arlan Hamilton, the founder of Backstage Capital, has a quote about culture and equity that will send chills down the spine of anyone who watches.

“We drive culture. You know how frustrating it is, to go into a venture capitalist’s office and have them blasting Drake, or blasting Tupac or quoting them in articles but not writing checks to black people? It’s frustrating. We’re trying to bypass all that, we’re trying to get to the point where we don’t even have to stop at their office anymore.”

Boss: The Black Experience in Business shows us that Black people are not just basic cogs in the American economic machine, but crucial parts of some of this country’s greatest achievements. Black people have been trailblazers. We’ve been disruptors. And Nelson brings our achievements, conquests, and innovations to life in a way that will last for generations.

Nelson’s next film will chronicle the life of Miles Davis, and will be in theaters this fall. Boss: The Black Experience in Business is streaming on PBS.org until May 22.